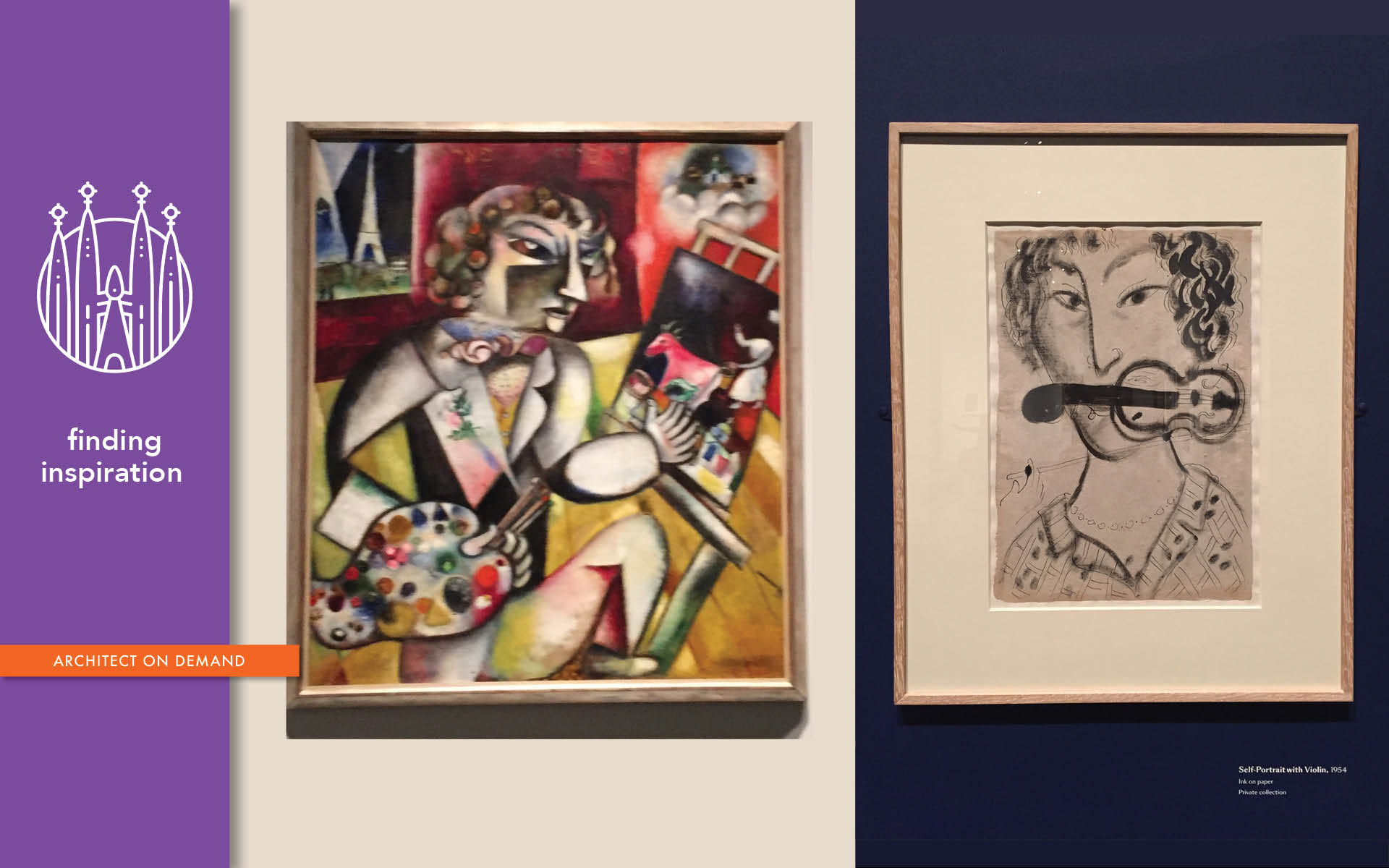

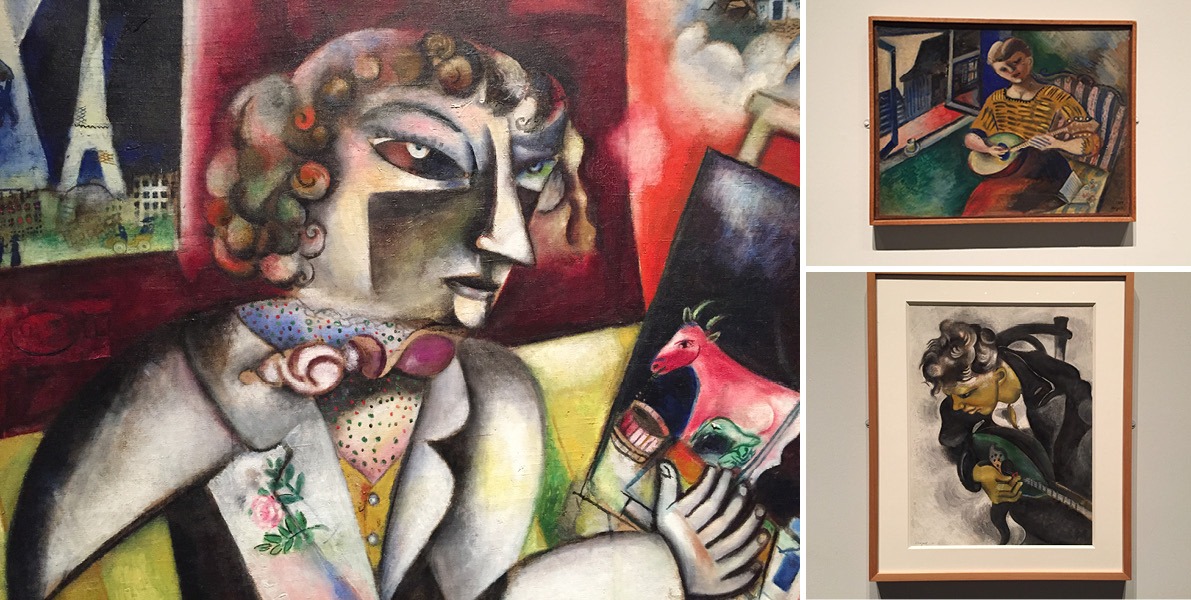

Marc Chagall: Self-Portrait With Seven Fingers

I am at LACMA’s Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage exhibit. Having seen it twice already, today I intend to focus on my favorite piece — Marc Chagall’s Self-Portrait With Seven Fingers — to take time, go deeper, and study it intently.

Who is this virtuoso holding his palette and paint brushes as if they were a violin and a bow? Why is he looking up? Is he kneeling? His face appears both tormented and exalted. Why seven fingers? He is in his studio working — why is he all dressed up, with a boutonniere in his lapel?

There’s a sense of divine presence in the painting. Is he praying?

It seems to me that the self-portrait is a self-exploration. A rendering of someone piously aspiring to delve into his creative potential, to affirm his calling as a painter. Hence, seven fingers — a sure way to do a good job. The artist is floating on air, hovering above the floor in a heightened state of intense emotion — in sheer ecstasy or bliss. As if in prayer, he is filled with joy and enthusiasm. He is dressed meticulously — taking his mission very seriously. A palette in a shape of a bird or a violin is his instrument — a way to give structure to his deepest feelings. Art is his music — a process through which he aims to accomplish a divine purpose.

This is Chagall’s very first self-portrait; painted in 1912-13, it depicts the precise moment of appealing for encouragement and approval.

The Old Testament forbade idolatry and was interpreted by Jews as an injunction against painting pictures. Chagall wrote: “No picture hung on our walls, not even a print… Until 1906, in all the years I spent in Vitebsk, I had never seen a single picture.”

In 1906, 19 years old at the time, Chagall was permitted to receive lessons from a portraitist in his home town, Vitebsk, a small provincial community with 60,000 inhabitants, over half of them Jews. Chagall recalled: “My uncle is too frightened to give me his hand. He has heard that I’m a painter. What if I wanted to paint him? God forbids such things. Sin.”

In his Self-Portrait With Seven Fingers Marc Chagall longs to be equated with violinists revered in the land of his birth.

Musicians are the ones held in high esteem in Jewish culture. His sister Lisa and brother David play a mandolin (or bandura); they conform to the Chassidic belief that music is a supreme channel through which to achieve communion with God. Chagall, on the other hand, choses another way and now he is all alone. While revealing a defiant essence, he is pleading for understanding, redemption. He is being judged.

Chagall is torn. He dares to assert a unique point of view while faithfully continuing the work passed on to him by his ancestors. The painting incorporates Hebrew lettering as if Chagall is expressing the Jewish ideal. He is asking for permission to articulate a vision of his own, to describe a dream world where fragments of personal reality defy gravity — singing and dancing.

I admire and am inspired by the virtuoso’s patience and engagement. Comparing Marc Chagall of 1954 (Self-Portrait with Violin) and of 1913 (Self-Portrait With Seven Fingers) on the cover image, I see continuity and cohesion. The artist succeeds; he matures staying on his path. Celebrating his joyously deep relationship with both music and painting is a life-long endeavor. Would you agree? Please share your own opinion in comments below or write to me here.